|

| From

the south |

| |

|

| The

Great Hall |

| |

|

| The

organ |

| |

|

| The

Crown Court |

|

| St. George's Hall |

| In 1839 and

1840, Harvey Lonsdale Elmes won competitions to

design both a concert hall and assize courts.

Liverpool Corporation then wanted the two

combined, which was good news for us, who have

inherited the present magnificent building, but

bad news for poor Elmes, who died in the process

of exhaustion and consumption at the age of only

33. St George's Hall is a neoclassical

masterpiece, 'one of the greatest [buildings] in

England and a monument of world importance'

(Quentin Hughes). Lewis's Topographical

Dictionary of England (1848) provides a

useful description: |

| |

St. George's Hall

[...] is in the Grecian style, 500 feet in

extreme length, and of very lofty elevation. The

east front [...] is embellished with a stately

and boldly projecting portico of sixteen columns

of the Corinthian order, supporting an enriched

entablature and cornice, which surrounds the

whole of the building, and affording an entrance

by a flight of steps into St. George's Hall,

which is in the centre, and the roof of which

rises to a considerable elevation above the rest

of the structure. |

| |

This hall is 169

feet in length, 75 feet in width, and 75 feet in

height, and during the assizes is open to the

public; it communicates at the north and south

ends with the assize courts, each of which is 60

feet long, 50 wide, and 45 high. On each side of

the portico are façades of square pillars,

between the lower portions of which are

ornamented screens rising to about one third of

the height. The south front consists of a noble

and boldly projecting portico of circular columns

of the Corinthian order, rising from a

richly-moulded surbase ten feet in height (which

surrounds the whole pile), and surmounted by a

pediment whose apex has an elevation of

ninety-five feet from the ground. |

| |

The north front,

which is semicircular, is also embellished with

Corinthian columns; this part of the building

contains a concert-room, seventy-two feet in

length, and nearly of equal breadth. The edifice,

in addition to the principal divisions, contains

the vice-chancellor's court, the sheriff's-jury

court, a grand-jury room, a barristers' library,

and other apartments; the whole, for the grandeur

of its dimensions, the loftiness of its

elevation, and the elegance of its style, forming

one of the most sumptuous and magnificent

structures in the kingdom. The estimated cost of

the building is £153,000, exclusive of the site:

architect, the late Mr. H. L. Elmes; contractor,

Mr. John Tomkinson. |

| The many

features of St. George's Plateau facing

Lime Street include four huge lions (Cockerell

1856), the equestrian bronzes of Queen Victoria

and Prince Albert (Thornycroft 1866-9) and the

dolphin-based cast-iron lamp standards (also by

Cockerell). Disraeli (Birch 1883) stands on the

steps. |

| St. Georges

Hall was re-opened to the public in 2007

following a major restoration costing £23

million. It is something no visitor should miss.

The largest room is the Great Hall, with

its organ, magnificent tiled floor (not usually

exposed) and ceiling. The organ was the biggest

in the country until the one in the Royal Albert

Hall in London was built in 1871. Two of the

original granite columns had to be removed to

install the organ and these were relocated to the

entrance of Sefton Park. |

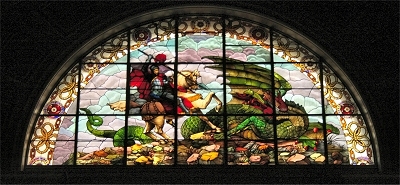

| The stained

glass at either end of the Great Hall, by Forrest

& Son of Liverpool, was added in 1883-4. At

the south end, appropriately enough, St. George

and the Dragon are depicted. The stained glass at

the north end is inspired by the Liverpool Coat

of Arms. I've yet to see a definitve version of

the latter - indeed there may not be one, but all

versions depict Poseidon (Neptune), god of the

sea, on the left and his son and messenger the

merman Triton, blowing on a conch shell, on the

right. In between are a cormorant and above it a

Liver Bird. The motto, from Virgil, reads Deus

nobis haec otia fecit, which translates

roughly as God has provided this leisure for

us. |

| It is

possible to visit the Crown Court, Judge's

Room, Grand Jury Room and the

prisoners' cells below; the latter are

atmospheric verging on harrowing. The courtroom

still operated as Liverpool's only criminal court

until 1984. |

| It is also

possible to visit the beautiful, circular,

Small Concert Room as an attendee at one of

the regular chamber concerts now being held

there. Charles Dickens recited and Franz Listz

performed there in the 19th century. |

|

|

| St.

George's Plateau |

| |

|

| Ceiling

of the Great Hall |

| |

|

| Stained

glass at the south end |

| |

|

| Stained

glass at the north end |

| |

|

| The

Crown Court |

|