|

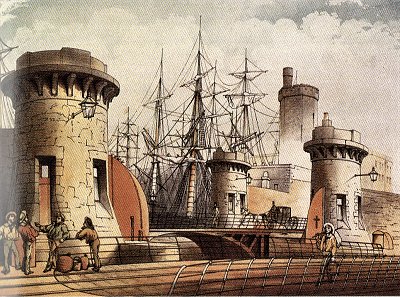

| Prince's

Dock, Half Tide Dock and the Waterloo Docks |

|

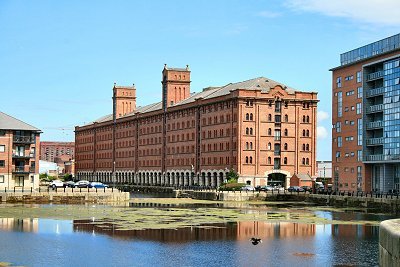

| The

Waterloo Grain Warehouse |

|

| The

Victoria Clock Tower and Stanley Dock Lift Bridge |

|

| Stanley

Dock Warehouse |

|

| The

Salisbury Dockmaster's Office |

|

| Pneumonia

Alley |

|

| The

Entrance Gates to Bramley-Moore Dock |

|

| The Development of the

North Docks |

| Construction of Prince's

Dock (named after the Prince Regent) by John

Foster began in 1810 but was only completed in

1821. It is shown on Sherriff's map along with

the adjacent Prince's Half Tide Dock. The latter,

with its lock gate to the Mersey, opened in 1810

but was rebuilt in 1868. Prince's Dock was closed

to shipping in the 1980s. |

| There has been sporadic

redevelopment of the dockside areas since 1988,

but according to the Pevsner Guide, 'The

architecture is both bland and overly fussy, and

the lifeless monoculture could be a business park

anywhere. Adjoining the Pier Head, architectural

standards should be far higher'. However, 2017

should see the start of the ambitious £300

million next phase of the Liverpool Waters

project in this area. |

| Next along, Waterloo

Dock opened in 1834, and was redeveloped into

east and west branches in 1868 (compare the 1836

and 1890 maps). It was designed, like the rest of

the docks discussed here, by Jesse Hartley and

named after the Battle of Waterloo. The Waterloo Grain

Warehouse of 1866-8 was designed by G.F. Lyster

and the overall facility constituted the world's

first bulk American grain handling facility. The

surviving warehouse, originally the easternmost

of three such, has been converted to apartments. The Waterloo Dock system closed to

shipping in 1988. |

| Next up were Victoria

Dock (after Princess, soon Queen, Victoria) and

its neighbour Trafalgar Dock (after the Battle of

Trafalgar), which opened together in 1836. The

former was altered in 1848 to remove its river

entrance. It was partly filled in in 1972 and the

remainder followed in 1988. The latter was used

as a landfill site in the early 1990s. |

| Clarence Half Tide Dock

was connected by a lock system to Trafalgar Dock

and on to Clarence Dock, Clarence Graving Basin

and two graving docks. They were named after the

Duke of Clarence, later William IV. They opened

in 1830 and were enlarged in 1853. They were

purpose-built steamship docks as a fire

prevention measure given that so many wooden

ships were using the docks to the south. The

docks closed in 1929 and, except for the graving

basin and graving docks, were filled in the

following year. The site was subsequently used

for the Clarence Dock Power Station, demolished

in 1994, whose three huge chimneys were a

Liverpool landmark. |

| On Gage's 1836, the

docks terminate here with landfill and a sea

wall. Regent Road petered out by the North Shore

Mill, where there were bowling greens. Between

there and Clarence dock was a Napoleonic

fortress, presumably built in the 1820s about the

same time as Fort Perch Rock at New Brighton, but

little spoken of. It was demolished in the next

phase of dock building. |

| The Salisbury,

Collingwood and Stanley Dock system of 1848 was

the next to be constructed. Salisbury Dock was a

half-tide dock connected to the river by two

locks and on to Collingwood Dock, named after

Vice Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood. The hexagonal,

castellated Victoria Tower, designed by Jesse

Hartley and completed in 1848, is a clock (one

per face) and bell tower that used to give time

to neighbouring docks and passing ships and ring

out high tide and warnings. It also provided a

flat for the piermaster. Here also is the former Dock

Master's Office, also built by Hartley using

masonry in his trademark Cyclopean style

(see below). |

| Collingwood Dock in turn

connects under a lift bridge to Stanley Dock,

named after the local family and the only one of

Liverpool's docks to be built inland, and on to

the Leeds and Liverpool Canal, thereby providing

a link from the canal to the river. An octagonal hydraulic

tower and pumphouse was used to provide power for

lifting devices, capstans, locks, bridges and

tobacco presses. Hartley's frequent use of

turrets, arrow slits and other trappings of the

mediaeval castle for such buildings was intended

to reinforce the impression of impregnability. |

| The Stanley

Dock warehouses, designed, like the Albert Dock

warehouses, by Jesse Hartley, were opened in

1856. The warehouse on the south side of the dock

was demolished and the dock partly filled in in

1901 to make way for the huge Tobacco Bonded

Warehouse. This vast building of 1901 designed by

A.G. Lyster is 12 storeys high and, with 27

million bricks, it is reputed to be the largest

brick building in the world. The narrow

passageway between it and the adjacent warehouse,

where the wind howls and the sun rarely shines,

was nicknamed Pneumonia Alley. At the

back, the Bonded Tea Warehouse, originally the

Clarence Warehouse, was Liverpool's largest

warehouse when constructed in 1844. These

warehouses form the last significant remnant of

what was once the characteristic landscape of the

dock hinterland. |

| Until recently

the whole area was derelict: 'easily the most

impressive and the most evocatively derelict dock

in Liverpool', according to the Pevsner Guide.

However it has been subject to a £130m

redevelopment with the north Stanley Dock

warehouse becoming a 4-star hotel. The next

phase, now (2017) under way, includes renovating

the Tobacco Bonded Warehouse, creating

apartments, bars and shops, and removing the

centre of the building to create a garden

courtyard. There are plans to redevelop the whole

area, as has happened

so successfully in the south docks. |

| Next to the north and

connected to Collingwood Dock are Nelson Dock and

Bramley Moore Dock, both of 1848. The latter was

named after John Bramley-Moore, chairman of the

dock committee, and brings us to the northern

edge of the Liverpool Borough. The dock walls and

entrance gates here are good places to examine

Hartley's Cyclopean style, extraordinarily intricate

stone construction reminiscent of dry stone

walling in its dovetailing of irregular blocks.

The periodic dock gates with their castellated

gatepiers were intended to give the impression of

impregnability and hence, not always

successfully, deter pilferers. Bramley Moore Dock also has a

large surviving Hydraulic Accumulator Tower, once

used to provide hydraulic power to drive

machinery. A heavy atmosphere of decay still

broods over much of the northern dock area. |

| The

Prince's dock, constructed under an act passed in

the 51st of George III, was opened with great

ceremony on the 19th of July, 1821, the day of

the coronation of George IV.; it is 500 yards in

length, and 106 in breadth. On the north is a

spacious basin belonging to it, and on the south

it communicates with the basin of George's dock:

at the north end is a handsome dwelling-house for

the dock-master, with suitable offices; and at

the south end a house in which the master of

George's dock resides. Spacious sheds called

'transit sheds' have been recently built on the

west quay, into which a ship may discharge her

cargo immediately on her arrival, under the

surveillance of the custom-house officers, the

goods to be afterwards distributed to the

different owners: by this convenience, much delay

is avoided. |

| Northward

of the basin belonging to this dock are three

docks called the Waterloo, the Victoria, and the

Trafalgar; the first was opened in 1834, and the

two others in 1836: the Trafalgar dock is

principally used for steam-vessels. Still further

in the same direction are the Clarence dock and

half-tide basin, completed in 1830, and

appropriated solely to steam-vessels frequenting

the port; also two capacious graving docks.

Beyond these graving docks, a vast accession of

accommodation is now in course of construction,

under the provisions of an act passed in the 8th

Victoria, consisting of eight separate docks and

six graving docks, the former having an aggregate

water area of above 60 acres, and quay space

measuring 3 miles and 257 yards in length. These

splendid docks will be capable of admitting

steamers of the largest class, and will

communicate, by a series of locks, with the Leeds

canal, an improvement of the greatest importance.

[TDE] |

|

|

| The

Waterloo Docks and Grain Warehouse |

|

| The

Stanley Dock Area and Tobacco Warehouse |

|

| Stanley

Dock Entrance and Policemen's Lodges c.1860 |

|

| The

Victoria Clock Tower and Salisbury Dock |

|

| Stanley

Dock Lift Bridge and Hydraulic Tower |

|

| The

Bonded Tea Warehouse |

|

| Hydraulic

Accumulator Tower at Bramley-Moore Dock |

|