| Liverpool Docks and Waterfront |

|

|||||||

| Liverpool Docks and Waterfront |

|

|||||||

|

|

Start at Sandhills Station [1] and walk down Sandhills Lane to Regent Road. Directly opposite is the wall of Huskisson Dock [2] in Jesse Harley's trademark Cyclopean granite, extraordinarily intricate stone construction reminiscent of dry stone walling in its dovetailing of irregular blocks. You will see much more of this throughout the walk. Turn left and walk along Regent Road, where you pass several of Hartley's characteristic triple-piered gates. After about 600 yds (m), notice the surviving hydraulic accumulator tower [3] at Bramley-Moore Dock, once used to provide hydraulic power to drive machinery. However, much of the northern dock area was obliterated during World War II. |

|

|

A little further along you reach the Stanley Dock area, a large surviving complex of nineteenth century buildings and waterways, largely the work of Jesse Hartley. Just before the Stanley Dock warehouse [4] (now the Titanic Hotel), it is worth a detour to the left, then to turn right along Great Howard Street and left through a gap in the wall, to have a look at the Leeds and Liverpool Canal lock system [5]. This extension was built by Hartley in 1848 to provide access to the Stanley Dock and onwards and consists of four locks descending 44 ft (13.5 m). Today it is a delightful and peaceful little haven. |

|

|

|

|

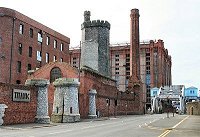

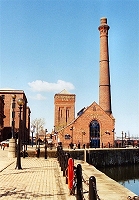

Return the same way to Regent Road and walk onto the Stanley Dock lift bridge [6]. Looking out towards the river, the Victoria Clock Tower [7] dominates with Salisbury and Collingwood Docks in the foreground. The hexagonal, castellated tower, designed by Jesse Hartley and completed in 1848, has a clock on each face to give time to neighbouring docks and passing ships and a bell to ring out high tides and warnings. Stanley Dock was the only one of Liverpool's docks to be built inland. The octagonal hydraulic tower and pumphouse was used to provide power for lifting devices, capstans, locks, bridges and tobacco presses. Hartley's frequent use of turrets, arrow slits and other trappings of the mediaeval castle for such buildings was intended to reinforce the impression of impregnability. On the other side of the dock, the vast Tobacco Bonded Warehouse [8] of 1901 is, with its 27 million bricks, reputed to be the largest brick building in the world. The narrow passageway between it and the next warehouse, where the wind howls and the sun rarely shines, was once nicknamed Pneumonia Alley. |  |

|

|

Continuing along Regent Road, you soon get a view over the Clarence Graving Docks [9]. Carry on along the road for just over half a mile (1 km) past the Waterloo Grain Warehouse [10] and turn right at a roundabout towards the river. Prince's Dock [11], completed in 1821, is on your left. On your right is the best view of the Waterloo Warehouse (1868) behind Prince's Half-Tide Dock [12], with Waterloo Dock the world's first bulk American grain handling facility. Continue down to the river with a fine view over Prince's Half-Tide Dock to the northern dockland, culminating in the new container base at Seaforth known as Liverpool Two. Walk along Prince's Parade, a nice stretch of riverside to the right but uninspiring modern architecture on the left. |  |

|

|

|

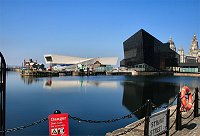

Emerge at the Pier Head and take in the splendour of the Three Graces: the Royal Liver Building [13], the Cunard Building [14] and the Port of Liverpool Building [15]. The famous Royal Liver Building was completed in 1911 for the Royal Liver Friendly Society. It is unique in design in this country, incorporating Baroque, Art Nouveau and Byzantine influences and drawing inspiration from some early American tall buildings. The clocks, 25 ft (7½ m) in diameter, were the largest electrically driven clocks in the UK when installed. The two iconic Liver Birds perched on the top are 18 ft (5½ m) high. The Cunard Building represents the restrained, elegant and Italianate face of the Three Graces and was the last to be completed in 1916 as the head offices and passenger terminal for the Cunard Steamship Company. The Port of Liverpool Building was originally the head office of the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board and was completed in 1907. It is constructed in Portland stone and its extravagance (inside as much as outside) did not go without criticism even in those more confident times. |  |

|

The Pier Head area has recently been completely and rather successfully reconstructed and the Leeds and Liverpool Canal extension from the Stanley Dock to the Albert Dock now runs through. There are various statues and memorials around here, such as the one of Edward VII. This is, of course, also a good place to watch the famous Mersey Ferries come and go. In front of you is the new Museum of Liverpool [16], well worth a look inside and it's free! It opened in 2011 and has since won a number of awards, most recently the Council of Europe Museum Prize for 2013. Walk by the riverside past the museum and the Pilotage Building [17] of 1883 onto the Canning Half-Tide Dock bridge. |

|

|

|

|

There were originally two locks to the river here but the northern one has been blocked. Beside the locks are three octagonal granite gatemen's shelters designed by Hartley. Inland, you look over Canning Half-Tide Dock [18] and Canning Dock [19] (1844 in their present form but originally much older). This area is the location of the mouth of the former tidal creek known as The Pool (from which Liverpool partly derives its name). Over the bridge, the first building is the Piermaster's House [20], the only one of many such to survive. Cross the Albert Dock entrance gates and walk along the Canning dockside for a better view of the docks; there are often sailing ships moored here. You come to the Pumphouse [21], formerly the Albert Hydraulic Power Centre, built in 1878 to provide high pressure water for hydraulic dock gates, bridges, lifts and cranes. The building has been restored as a pub and outside is a great place to sit with a drink. |  |

|

|

Return to the Albert Dock entrance gates, noting the Grade I Listed Dock Traffic Office [22] with its Greek temple-like frontage, built in 1848. The portico is made of cast iron, the pillars being in two sections each and the architrave above a single casting. Just before the entrance gates, turn left into the Albert Dock [23], the first view of which will undoubtedly impress. The monumental warehouses were opened in 1845 and built to last at huge expense. Hartley's fireproof design was a reaction to the enormous losses previously sustained in warehouse fires. It also allowed direct loading and unloading between ships and warehouses for the first time in Liverpool. The building on your immediate left is the Merseyside Maritime Museum, which tells the story of Liverpool's seafaring heritage. On the other side of dock gates is Tate Liverpool, the largest modern art gallery in the UK outside of London. |  |

|

|

Go around the north-east corner of the dock and exit half-way along onto the side of Salthouse Dock [24]. Walk along and turn to the left for a better view. This was the first of the south docks, completed in 1753, and is the oldest still in existence. The name came from the saltworks and it was important for the landing of rock salt from Cheshire, which was refined in Liverpool and transported onwards. Return and continue alongside narrow Duke's Dock [25] (1773) on the left. This was built for the Duke of Bridgewater to serve the Bridgewater Canal, which had been extended to the River Mersey at Runcorn. The first of Liverpool's dockside warehouses was built here in 1783 and it has the most complete surviving 18th century dock retaining walls in Liverpool. |  |

|

|

|

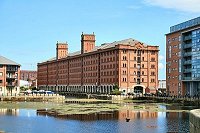

Cross Duke's Dock via the bridge by The Wheel of Liverpool [26], well worth a ride for the views. In the early 21st century this area became a major brownfield development site, culminating in the opening in 2008 of the Echo Arena and BT Convention centre [27]. Walk back to the next bridge over Duke's Dock and turn right through the modern developments to reach Wapping Dock [28] with its fine warehouse opposite. Completed in 1856, the building originally had forty bays divided into five fireproof sections, but was reduced in length following wartime bombing damage, as can be seen from the surviving iron colonnade on the quayside. Turn left at the end of the dock and walk up to the gates on the main road to have a look at Hartley's fanciful Wapping Hydraulic Tower and Policeman's Lodge [29] of 1856, standing there like some giant surreal chess pieces. |  |

|

|

|

To the south of you is the vast but rather uninteresting Queen's Dock [30], originally built in 1785 but much altered and extended since. Walk alongside Queen's Dock until blocked from further progress by The Keel [31], then head towards the river. Completed in 1993 and not particularly beautiful, The Keel is the home of Customs and Excise offices and is the latest in a long line of customs houses on the docks. It was built over and incorporates the old Queen's Graving Dock. Now head along the riverside. Next to The Keel is Queen's Branch Dock No. 1 [32]. |  |

|

|

A short way along the river is a little inlet, the South Ferry Basin or Cocklehole [33] (c.1820), built for ferries and fishermen and unaltered since. Here you have a fine view over the marina in Coburg Dock [34], originally opened in 1840. Further on is the entrance to Brunswick Half-Tide Dock [35] (now filled in) complete with two octagonal gatemen's shelters. A little further on again is the surviving one of two lock gates [36] to Brunswick Dock [37], Jesse Hartley's first, which opened in 1832 and was initially used for importing timber. It is the most southerly of the surviving docks. |  |

|

|

Now head alongside Brunswick Business Park, built on top of the filled in Toxteth and Harrington Docks for just over half a mile (1 km) to reach a prominent Chinese Restaurant [38], recommended for good food and fabulous views up and down the River Mersey. This was built on an island between two locks (since filled in) serving the Herculaneum Dock of 1866. The site had been a tidal basin of 1767 serving a local copper smelting works. From 1794 to 1841 it was the location of the famous Herculaneum Pottery. From 1873 the dock handled petroleum and special storage facilities were built in the sandstone cliffs behind. From here make for Sefton Street, where Century Building [39] is one of the few surviving of the original Harrington Dock buildings. Opposite is the Dingle Tunnel Entrance [40] of the old Overhead Railway, an almost unique remnant of this vast engineering feat. Turn left along Sefton Street for the end of the walk at Brunswick Station [41] and direct trains back to the start at Sandhills. If you like, you can continue along the riverside as far as possible and then head through Grassendale Park to Cressington Station. This adds 2½ miles (4 km) to the walk. |  |

|